What is a Trial Balance?

A trial balance is an internal accounting report that lists every account in your general ledger along with its balance at a specific point in time. It shows the total debits in one column and the total credits in another, allowing you to quickly see if your books are mathematically correct.

In double-entry accounting, each transaction records equal debit and credit amounts. The trial balance checks that these amounts match. If the totals are not equal, it signals an error that needs to be found and corrected before you move forward.

Within the accounting cycle, the trial balance is prepared after all transactions have been posted to the ledger and before any financial statements are created. It is an internal document used to verify accuracy and is not shared with investors, lenders, or tax authorities.

Beyond simply verifying the math, the trial balance also provides a clear, organized view of your accounts in one place. This makes it easier to review account balances, spot irregularities, and prepare for the next steps in the accounting process, such as making adjusting entries or closing the books.

Why is a Trial Balance Used? (Purpose & Importance)

A trial balance plays an important role in keeping your accounting records accurate and reliable. Here are the main reasons it is used:

1. Helps in Error Detection

One of the first things a trial balance does is act like a red flag for mistakes in your books. If the total debits and total credits do not match in your trial balance, something is off and needs to be fixed. This mismatch alerts you that an entry was recorded incorrectly and needs to be corrected before moving forward.

2. Foundation for Creating Financial Statements

The trial balance provides the figures you need to prepare your income statement, balance sheet, and other financial reports such as a compilation report. Without it, you risk basing your statements on incomplete or inaccurate data.

3. Confirmation of Double-Entry

It ensures that every transaction recorded in your accounting system follows the double-entry rule, where each debit has an equal and corresponding credit. This confirmation helps maintain the integrity of your financial data.

4. Serves as Internal Control

Because it is an internal document, the trial balance acts as a checkpoint for your accounting team. It gives you a chance to catch and correct issues before they impact your official financial statements.

5. Preparation for Adjusting Entries

Before you make adjusting entries for accruals, deferrals, or corrections, you need an accurate trial balance. This ensures your adjustments are applied to the correct account balances.

Types of Trial Balances

There are three main types of trial balances you might prepare during the accounting cycle. Each serves a different purpose and happens at a specific stage in the process.

Here’s a quick reference table that gives an overview of each type of trial balance.

| Type | When It’s Prepared | What It Includes | Why It’s Used |

| Unadjusted Trial Balance | After posting all transactions to the ledger, before adjustments | All accounts with their initial debit and credit balances | To check if total debits equal total credits before making any adjustments |

| Adjusted Trial Balance | After making all adjusting entries | All accounts with updated balances after adjustments | To ensure account balances are accurate before creating financial statements |

| Post-closing Trial Balance | After closing temporary accounts at the end of the period | Only permanent accounts (assets, liabilities, equity) | To confirm debits and credits still match before starting a new accounting period |

1. Unadjusted Trial Balance

The unadjusted trial balance is prepared right after all transactions have been posted to the ledger. It shows the initial balances before any adjustments are made for accruals, deferrals, or errors. Its main purpose is to check if total debits equal total credits at this stage and to identify any obvious posting mistakes.

2. Adjusted Trial Balance

The adjusted trial balance comes after you have made all necessary adjusting entries, such as recording depreciation, accruals, or prepaid expenses. This version reflects the most accurate account balances and is used as the basis for creating your financial statements.

3. Post-closing Trial Balance

The post-closing trial balance is prepared after all temporary accounts, like revenues and expenses, have been closed to retained earnings. Only permanent accounts, such as assets, liabilities, and equity, remain. Its purpose is to confirm that debits and credits still match before starting a new accounting period.

Rules for Preparing a Trial Balance

When preparing a trial balance, following a few basic rules will help you avoid errors and keep your records clear.

a. All Accounts Included

Make sure you include every active account from your general ledger. This covers assets, liabilities, equity, revenues, and expenses. Leaving out an account, even if it has a zero balance, can create confusion and make your totals inaccurate.

b. Debit and Credit Columns

List debit balances in one column and credit balances in another. This clear separation makes it easy to compare the totals and confirm they match. For example, assets and expenses usually have debit balances, while liabilities, equity, and revenues typically have credit balances.

c. Normal Balances

Each account type has what is called a “normal balance,” which determines whether its balance is recorded in the debit or credit column. Knowing these makes it easier to place amounts in the right column. Here’s where each account type goes:

| Account Type | Normal Balance |

| Assets | Debit |

| Expenses | Debit |

| Liabilities | Credit |

| Equity | Credit |

| Revenue | Credit |

d. Summation

The total of the debit column must be exactly equal to the total of the credit column. If the two totals are not the same, there is an error that needs to be found and corrected before moving forward.

e. Timing

A trial balance is usually prepared at the end of an accounting period, such as month-end, quarter-end, or year-end, after all transactions for that period have been recorded.

f. Sequence

Accounts are typically listed in the same order as they appear in the Chart of Accounts. This means starting with assets, followed by liabilities, equity, revenue, and finally expenses.

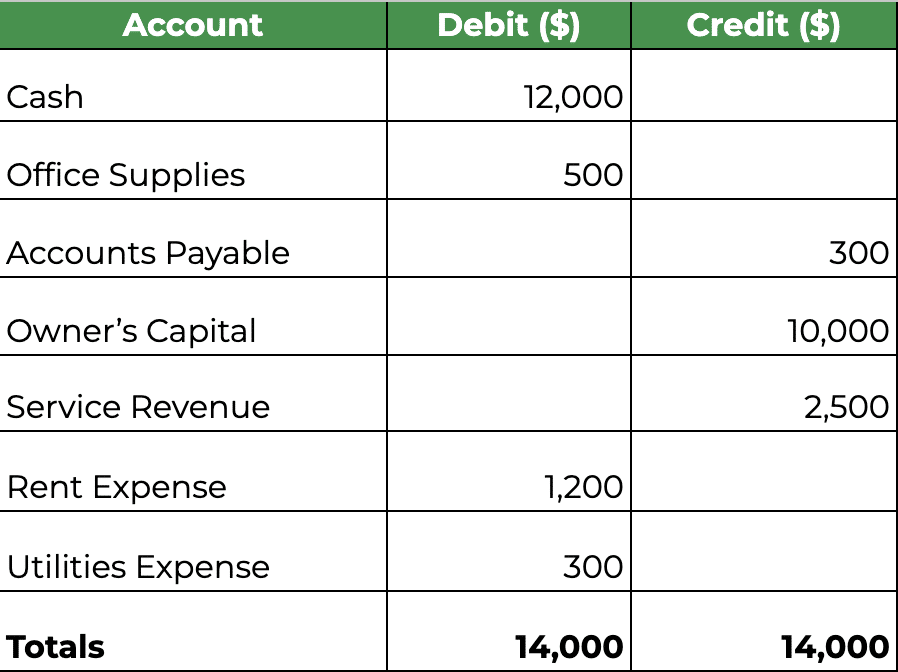

Example of a Trial Balance

One of the best ways to understand a trial balance is to see it in action. The goal is to show how transactions flow from the journal to the ledger and finally into a trial balance, where you can check if everything is in balance.

In this example, we’ll look at a small hypothetical business and walk through a few transactions. This will help you see how the debit and credit columns are filled, how account balances are categorized, and how the final totals confirm the accuracy of your books.

Let’s say Bright Books Consulting, a small accounting firm, has recorded the following transactions during its first month:

- The owner invests $10,000 in cash to start the business.

- The firm buys office supplies for $500 cash.

- The firm earns $2,500 in service revenue from clients, paid in cash.

- Pays $1,200 for office rent.

- Receives a $300 utility bill, which will be paid later.

After posting these transactions to the general ledger, the trial balance at month-end would look like this:

| Account | Debit ($) | Credit ($) |

| Cash | 12,000 | |

| Office Supplies | 500 | |

| Accounts Payable | 300 | |

| Owner’s Capital | 10,000 | |

| Service Revenue | 2,500 | |

| Rent Expense | 1,200 | |

| Utilities Expense | 300 | |

| Totals | 14,000 | 14,000 |

What This Example Shows

- Normal Balances: Assets (Cash, Office Supplies) and Expenses (Rent, Utilities) are in the debit column, while Liabilities (Accounts Payable), Equity (Owner’s Capital), and Revenue are in the credit column.

- Equal Totals: The debit total of $14,000 matches the credit total of $14,000, which confirms the books are in balance.

- Internal Checkpoint: If the totals didn’t match, it would indicate a posting error or omission that needs correction before preparing financial statements.

Common Errors in Trial Balance

Even though a trial balance helps you check that your books are in balance, it doesn’t catch every type of mistake. Some errors will still leave the debit and credit totals equal but misstate your accounts. Here are the most common ones and how to fix them:

I. Errors of Omission

An error of omission happens when a transaction that should have been recorded is left out entirely. Since neither the debit nor the credit side is entered, the trial balance totals still match, which makes this type of error harder to spot. The problem is that your records are incomplete, which can lead to inaccurate financial statements and poor decision-making.

Example: You receive a $300 utility bill in January but forget to record it in your books. Both the debit to Utilities Expense and the credit to Accounts Payable are missing. The trial balance still balances, but your liabilities and expenses are understated.

How to Correct It: Identify the missing transaction by reviewing source documents (invoices, receipts, bank statements) and post it to the correct accounts.

II. Errors of Commission

This happens when the correct transaction amount is recorded but placed in the wrong account of the same category. Since the debit and credit amounts are still equal, the trial balance totals remain in balance. However, the details within your accounts are incorrect, which can distort your financial reporting and make it harder to track specific costs or revenues accurately.

Example:

You pay $1,200 for office supplies but accidentally record it under “Equipment” instead of “Office Supplies.” Both are asset accounts, so the total debits and credits still match, but your office supplies expense is understated, and your equipment balance is overstated.

How to Correct It: Reverse the incorrect entry and record it in the correct account.

III. Compensating Errors

A compensating error occurs when two or more mistakes offset each other mathematically, leaving the total debits and credits in the trial balance equal. This type of error is particularly tricky because the trial balance appears perfectly balanced, even though the individual accounts contain inaccuracies.

Example:

You accidentally understate revenue by $200 and, in a separate error, understate expenses by $200. The $200 understatement in revenue reduces credits, and the $200 understatement in expenses reduces debits. These two errors cancel each other out in the totals, so the trial balance still balances, but both revenue and expense accounts are incorrect.

How to Correct It: Review each account individually rather than relying only on the trial balance totals. A detailed ledger review or account reconciliation will uncover these.

IV. Principle Errors

A principle error occurs when a transaction is recorded in violation of generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) or other established accounting rules. The amounts on the debit and credit sides may still match, so the trial balance totals remain equal, but the classification or treatment of the transaction is wrong. This type of error affects the accuracy of your financial statements and can lead to misleading results.

Example:

You purchase a machine for $5,000, but instead of recording it as an asset under “Machinery and Equipment,” you record it as an expense under “Repairs and Maintenance.” While the debit and credit amounts still match, this misclassification means you are understating your assets and overstating your expenses, which directly impacts net income and the balance sheet.

How to Correct It: Adjust the entry to align with proper accounting treatment, ensuring assets, liabilities, income, and expenses are classified correctly.

Remember, a trial balance is an important checkpoint, but it’s not foolproof. Regular bank reconciliations, review of source documents, and a solid understanding of accounting principles are still essential for accurate financial reporting.

Conclusion

The adjusted trial balance is the final checkpoint before you create your financial statements, ensuring your records are complete, accurate, and ready for reporting. Without it, you risk building financial statements on errors that could have been caught and corrected earlier in the process.

In the bigger picture of the accounting cycle, accuracy depends on having reliable processes at every stage. If tasks are scattered, deadlines slip, or staff are stretched thin, mistakes can easily make their way into your trial balance and beyond. That’s where Financial Cents accounting practice management software comes in.

With Financial Cents, you can track every client task and project in one place, set and monitor deadlines to ensure nothing is missed, and automate client reminders to save time on follow-ups. It also allows you to see the workload across your team to prevent burnout, standardize processes with workflow templates, and maintain clear communication and accountability across your firm.

When you put the right systems in place, you can focus on higher-value work, knowing your accounting process, from the first transaction to the adjusted trial balance, runs smoothly every time.

Start using Financial Cents to manage your accounting processes.