What is equity in accounting?

Equity is the owner’s (or shareholders’) claim on the business’s assets. It’s what’s left after all liabilities are accounted for, essentially, the client’s true stake in the company. It’s also the third pillar of the accounting equation (Assets = Liabilities + Equity).

It’s one of the most common concepts clients struggle to understand, and one you’re often asked to explain.

As your client’s trusted advisor, you’re often the one fielding questions like, ‘Why is my equity negative if my business made money?’ or ‘If I have equity, why can’t I just withdraw that amount as cash?’

Innocent as they are, these questions reveal genuine concerns about how their business is being managed, and they highlight a deeper misunderstanding of how equity in accounting really works. That’s why having a firm grasp of the subject is key.

As you know, equity isn’t static. It shifts with every profit earned, loss taken, capital contributed, or draw made, and that’s exactly where your clients often need clarity. Each of these movements reflects the business’s financial direction. For firm owners like you, understanding equity inside and out means you’re better equipped to provide strategic advice, support long-term planning, and deliver the kind of clarity that keeps clients coming back.

So let’s break down all you need to know about equity in accounting.

Components of Equity: By Business Structure

1. Sole Proprietorship / Partnership Equity

In sole proprietorships and partnerships, equity is typically referred to as the owner’s equity (for sole proprietors) or the partner’s equity (for partnerships). While the terminology differs slightly, the concept remains the same. It represents the owner’s or each partner’s claim on the business after liabilities are paid.

For example, if your client runs a small design studio as a sole proprietor and the business has $80,000 in total assets and $30,000 in outstanding liabilities, the owner’s equity would be $50,000. That $50,000 reflects the owner’s financial stake in the business, the amount they would theoretically walk away with if the business were liquidated today.

Because these business types don’t have shareholders, there’s no concept of stock or retained earnings in the traditional corporate sense. Everything flows directly through to the owner(s), making equity management more personal and often more fluid.

For sole proprietors, equity usually includes:

- Initial capital contributions – The original funds or assets the owner invested to start the business.

- Additional investments over time – Extra money or resources the owner puts into the business after startup.

- Accumulated profits (or losses) – Net income earned or losses incurred that increase or reduce equity over time.

- Owner’s drawings – Withdrawals taken by the owner for personal use, which reduce the total equity in the business.

In partnerships, each partner has their own capital account, and the equity section reflects:

- Their share of capital contributions

- Their share of profits and losses, based on the partnership agreement

- Any withdrawals or distributions

When managing the books for these business structures, equity typically consists of three key components:

- Capital Account: This tracks the initial and ongoing investments made by the owner(s) into the business. It forms the foundation of their ownership stake. It is located in the equity section of the balance sheet for a sole proprietorship or partnership.

- Drawings Account: Any time funds or assets are withdrawn for personal use, they’re recorded here. These aren’t business expenses, they reduce the owner’s equity directly.

- Net Income or Loss: Profits add to equity, while losses reduce it. Since income passes directly to the owners, these amounts flow straight into their capital account, rather than being retained within the business.

You can summarize the movement in equity with this simple formula:

Beginning Capital + Net Income – Drawings = Ending Capital

This formula helps you show clients, in black and white, how their actions (and business results) are shaping their equity position. It’s especially useful during reviews for year-end discussions when they want to understand where the money went and how their investment is growing (or shrinking).

2. Corporation Equity

In corporations, equity takes on a more structured form known as shareholders’ equity. Unlike sole proprietorships or partnerships, where equity is tied directly to individuals, corporate equity is divided among shareholders, based on the number and class of shares they hold.

This means that the majority shareholders (those who own more than 50% of the company’s outstanding shares) hold a controlling interest and a proportionally larger claim on the company’s equity and retained earnings than the minority shareholders, who own a smaller portion and have a proportionate but limited claim. Both groups are entitled to dividends (if declared) and a share of residual assets if the company is liquidated, but their level of influence and financial return depends on the size of their equity stake.

Shareholders’ equity represents the residual interest in the company’s assets after all liabilities are paid. It’s what belongs to the shareholders collectively, and it’s reported in the equity section of the balance sheet.

Corporation equity is typically divided into two main categories: Contributed Capital and Earned Capital. Let’s walk through the key components you’ll find in a corporation’s equity section:

a. Contributed Capital (Paid-in Capital)

This reflects the total capital that shareholders have invested in the company in exchange for stock. It includes:

- Common Stock

This represents the par value of shares issued to common shareholders. Common shareholders typically have voting rights and share in the company’s residual profits.

- Preferred Stock

These shares often come with fixed dividend rights and take priority over common stock in the event of liquidation. Preferred shareholders usually don’t have voting rights but enjoy a more stable income stream.

- Additional Paid-in Capital (APIC)

This is the amount shareholders paid above the stock’s par value. For example, if a share’s par value is $1 but an investor paid $10, the extra $9 goes into APIC. It reflects the true economic value contributed by shareholders beyond the minimum stated capital.

b. Earned Capital

This section reflects the profits the company has generated and retained over time. It includes:

- Retained Earnings

These are the cumulative profits (or losses) that haven’t been distributed as dividends. A growing retained earnings balance typically signals a healthy business reinvesting in itself, but it can also be a point of discussion if shareholders expect returns.

- Dividends

When a company pays out a portion of its earnings to shareholders, it reduces retained earnings. Tracking dividends is key for transparency and for reconciling changes in equity over time.

c. Other Components of Shareholders’ Equity

- Treasury Stock

These are shares the company has repurchased from shareholders. Treasury stock reduces total shareholders’ equity and may be held for future reissuance or to reduce dilution.

- Accumulated Other Comprehensive Income (AOCI)

This section captures gains and losses not included in net income, such as foreign currency adjustments, unrealized gains/losses on certain investments, and pension plan changes. AOCI gives a fuller picture of the company’s performance, especially in complex or global businesses.

Each of these components reflects not just what shareholders have put in, but how the business has performed over time. As their accountant or advisor providing client accounting services, helping your corporate clients understand how these elements interact is crucial, especially when they’re seeking funding, issuing dividends, or preparing for audits.

Ultimately, shareholders’ equity gives a clearer picture of a company’s long-term value, financial discipline, and ability to return value to investors.

Equity on Balance Sheet

On the balance sheet, equity shows your client’s true financial stake in the business. You’ll typically find equity positioned at the bottom of the balance sheet, right after total liabilities. It represents the owners or shareholder’s claim on the business after debts are paid. It also shows how much of the business is financed by the owners/shareholders rather than creditors.

In a corporate balance sheet, equity is often broken down into specific components. The two most common are Common Stock and Retained Earnings.

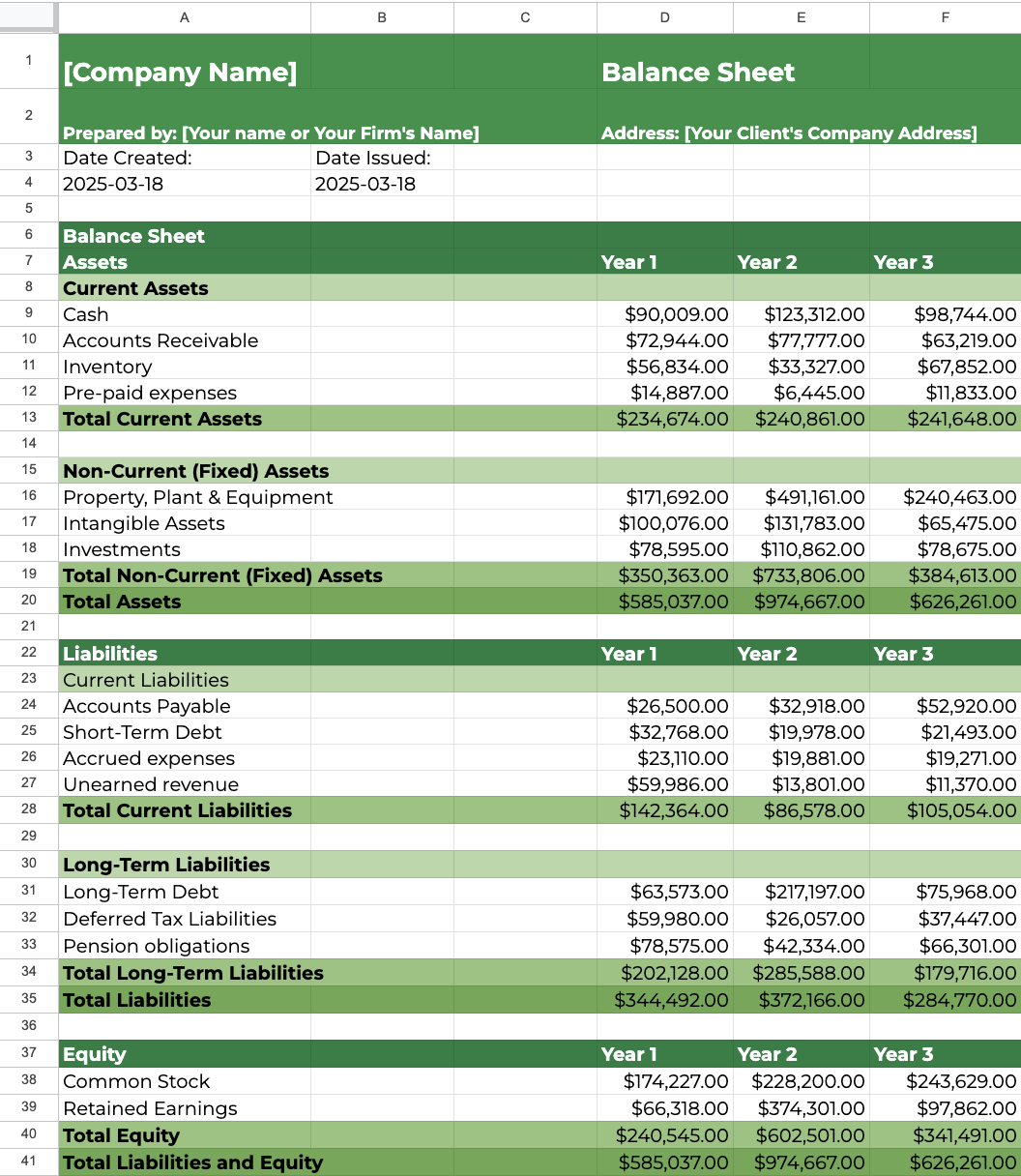

Take a look at this sample equity section from this three-year balance sheet template:

As you can see, the equity figures change from year to year. The increase in common stock suggests additional shares were issued. Meanwhile, fluctuations in retained earnings reflect the company’s net income performance and dividend decisions. A strong jump in retained earnings in Year 2, for instance, may point to high profitability or a decision to retain rather than distribute profits.

Altogether, these equity figures are added up to calculate Total Equity, which completes the accounting equation: Assets = Liabilities + Equity.

For you as an accountant or bookkeeper, walking clients through this section of their financials helps demystify how profits, owner actions, and financing decisions are impacting their business’s value. It’s a moment to bring clarity and add strategic value during reporting and planning conversations.

To help you apply this in real time, download our free, detailed Balance Sheet Template (available in Excel & Google Sheets) to practice with or use directly with your clients.

How Is Equity Calculated?

Equity is calculated using a simple formula:

Equity = Total Assets – Total Liabilities

This formula applies to all business types, but how equity is presented and what it represents varies based on the business structure.

Sole Proprietorship / Small Business

In a sole proprietorship, equity is referred to as owner’s equity. It represents the owner’s personal financial interest in the business. Since there are no shareholders or issued stock, equity is tracked through capital contributions, business profits or losses, and owner withdrawals.

Let’s say you’re preparing a balance sheet for a small retail business. The company has total assets of $120,000 and total liabilities of $45,000. Applying the formula:

$120,000 (Assets) – $45,000 (Liabilities) = $75,000 Owner’s Equity

But that $75,000 is not just about what the business owns today. It reflects how much the owner has invested, how much profit has been earned over time, and how much has been withdrawn for personal use. You might present this in more detail using an equity movement calculation:

Beginning Capital ($60,000) + Net Income ($25,000) – Drawings ($10,000) = Ending Capital (Owner’s Equity): $75,000

This approach is especially helpful when discussing equity with clients who may not understand why their net income doesn’t match their available equity. It also creates a cleaner audit trail for tax preparation and year-end planning.

Corporations

For corporations, equity is more structured and includes several distinct components, typically grouped under shareholders’ equity. This includes money invested by shareholders, profits the business has retained, and any equity adjustments such as stock buybacks or comprehensive income.

Imagine you’re reviewing the books for a growing tech startup. The company has total assets of $850,000 and total liabilities of $525,000. Equity would be calculated as:

$850,000 (Assets) – $525,000 (Liabilities) = $325,000 Shareholders’ Equity

To explain that $325,000 to your client or their investors, you’d break it down into its components:

- Common Stock: $150,000

- Additional Paid-In Capital (APIC): $25,000

- Retained Earnings: $175,000

- Treasury Stock: –$25,000

- Total Shareholders’ Equity: $325,000

Each of these figures gives insight into the company’s financial structure. Common stock and APIC reflect how much money investors have put into the company. Retained earnings show how much of the company’s profit has been reinvested rather than distributed as dividends. Treasury stock represents shares the company has repurchased, reducing total equity but often signaling confidence in future performance.

For your corporate clients, this level of detail is important, especially if they’re seeking funding, planning to issue dividends, or preparing for an audit. Understanding the composition of equity helps them make more informed decisions and helps you deliver more strategic guidance.

Why Equity Matters in Accounting

For your clients, equity plays a central role in understanding both where the business stands today and what’s possible for the future.

1. It serves as an indicator of business value and solvency.

When assets significantly outweigh liabilities, it reflects positively on the company’s financial stability and creditworthiness. A strong equity position shows that the business is not overly dependent on debt and can meet its obligations. For clients, this directly impacts how much their business is worth and how others perceive its financial health.

2. It reflects profitability over time.

Retained earnings accumulate in equity. This makes the equity section a running tally of how well the business has performed. A consistently increasing equity balance usually points to sound financial management and sustainable growth, while a declining one can indicate recurring losses or excessive withdrawals.

3. It indicates a company’s financial cushion and ability to repay debt.

Equity provides a buffer in tough times. Lenders and investors often use it to evaluate the business’s capacity to absorb losses or repay debt. A high equity-to-debt ratio suggests lower risk and often results in more favorable financing options.

4. It helps identify capital available for reinvestment and growth.

A healthy equity position means more internal capital to fund expansions, new projects, or operational improvements without relying entirely on external financing. This gives clients more flexibility and control over how they grow.

As an advisor, your ability to interpret equity and communicate what it means in practical terms is key. It positions you as a strategic partner helping clients build more resilient, forward-looking businesses.

How Do Accountants Track and Report Equity?

As your client’s accountant or bookkeeper, you’re responsible for more than just calculating equity; you’re also tracking its every movement and ensuring it’s accurately reported. That process starts with your general ledger, often managed through accounting software like QuickBooks or Xero.

In QuickBooks and similar accounting platforms, the general ledger serves as the central hub for all equity-related transactions. Whether it’s a capital injection, a shareholder draw, net income, or a dividend payment, it all flows through equity-related accounts. For sole proprietorships and partnerships, that means updating capital and drawing accounts for each owner or partner. In corporations, you’re managing multiple equity accounts, common stock, additional paid-in capital, retained earnings, and treasury stock, to name a few.

You also rely on journal entries to record these movements in real time. When owners contribute or withdraw funds, you enter those transactions to reflect the impact on equity. At the end of each accounting period, net income or loss is closed into retained earnings, ensuring that the business’s profitability is reflected in its equity position. If dividends are declared and paid, those are recorded as a reduction in retained earnings, not as expenses, but as equity adjustments.

Tracking retained earnings accurately is especially important. This account builds up over time and gives a long-term view of how well the business is retaining profit. Mistakes here can throw off financial statements, mislead stakeholders, and affect key decisions like dividend policies or loan approvals.

That’s why accurate reporting and regular reconciliation are non-negotiable. You need to make sure that your equity accounts align with the financial reality of the business.

Conclusion

At its core, equity tells the story of ownership, profitability, and long-term stability. Because equity is constantly moving, you must track these movements consistently across all your clients. Inaccurate or delayed updates can lead to misinformed decisions and unnecessary backtracking. To streamline this process and reduce the risk of missed steps, consider using an accounting practice management solution like Financial Cents.

With it, you can create standardized workflows for monthly financial statement preparation, ensuring equity updates are always accounted for. You can also set up recurring tasks (for instance, tracking year-end reconciliations) to stay ahead of key deadlines without relying on memory or manual reminders.

Financial Cents also helps you improve team collaboration, especially when multiple staff members are working with clients. Everyone stays aligned through internal comments and status updates. Plus, built-in audit trails and documented processes promote accountability, so you always know who did what, and when.

In the end, equity may belong to your clients, but keeping it accurate, clear, and actionable is your responsibility. And with the right tools like Financial Cents, you can make that process seamless, scalable, and client-ready.